I lost my father this year: six words that ripped a hole in my heart.

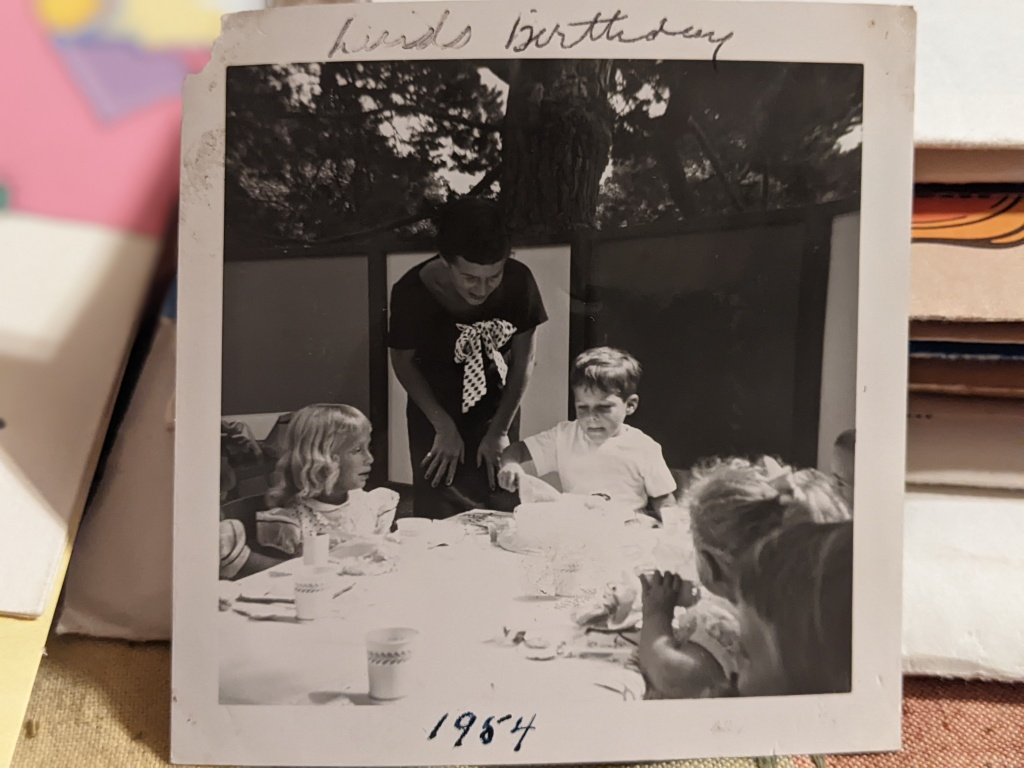

My dad, Laird Buchanan Craig, was born to Scottish parents Erwin Gibson (E.G.) Craig and Sheila Prentice Craig on August 26, 1950, in Oakland, California. He grew up in the East Bay, the oldest of four children: Christie, Gavin, and Ian. He graduated in 1968 from Acalanes High School in Lafayette before going to college at Claremont McKenna and transferring to UC Berkeley. He was a journeyman contractor, starting in construction at a young age, owning a few businesses over his lifetime. He married his college sweetheart, Kristin Doreen Meub, in 1972, with whom he had three children, Bonnie, Mary, and Katrin. He remarried Ella Wolfe in 2012, and retired a few years later. He died on March 7, 2022, from metastatic cancer. He loved nature, animals, waterskiing, snowboarding, learning, reading, people, and took great pride in his work.

That’s barely scratching the surface of a life fully lived, as my choppy sentences convey, but those were some of the broad strokes of his life.

How do you convey the true impact someone has, who shaped you into the person you are today? You can’t, always; some things are impossible to fully express. They are intransmissible memories. We try to share them, however much in vain, as I did during my father’s eulogy on April 8 at St. Anselm’s Epispocal Church in Lafayette, as follows:

Welcome everyone, and thank you so much for being here today.

I am Katrin Deetz, Laird Craig’s youngest daughter. Those of you here today either knew my dad by doing something fun and athletic, like water skiing or snowboarding, or perhaps you shared a lively debate about a current event, or maybe you worked in construction with Laird, witness to his craft and expertise in that domain; or maybe he helped you when you really needed some compassion. Perhaps you were lucky enough to share all of those things with him and more. He was a force of positivity for so many, with a passionate spirit and tenacious thirst for knowledge.

He was also known for being adventurous. My dad often said to me:

Drive fast, take chances, safety third.

He first said this when I got my driver’s license, but he might as well have been talking about his approach to life. Seventy-one years, and every one of them were spent chasing something more; squeezing the most out of the day; learning as much as he possibly could. Laird Buchanan Craig, my father, has influenced so many people throughout his life, spreading his zealous love of knowledge, Nature, and people.

To all three of us daughters, Bonnie, Mary, and me, he was a hero, both figuratively and literally. When I was a kid, I had a scary near-drowning experience kneeboarding. I had the strap too tight and too high around my hips, and took a hard fall. Flipping over face-first into the water, I couldn’t release myself from the strap; more urgently, I couldn’t breathe with my head underwater. Gasping frantically for air and stuck in the kneeboard, barely able to catch a breath before being smacked face down underwater again, I glimpsed my father diving out of the boat. I knew he was coming to save me, and though I was still fighting to not drown, I knew I would be okay (and I was, clearly).

My dad taught all of us what a strong work ethic looks like, too. My sister Mary and I spent a few Summers working on my dad’s construction sites, giving us the confidence to work hands-on with tools; I’ll never forget the day he let me drive his Ford truck through AppleHill in Brentwood, four-wheeling through the mud where his co-worker John McAustland had gotten stuck earlier. Today, Mary works in architecture and interior design, tackling home projects along the way, a passion definitely influenced by my father’s positive encouragement over the years. My father was also an anchor for my sister Bonnie as she pursued her education, earning a PhD in American Studies & American Literature, and authoring a book before going on to teach as a professor. He was a consistent anchor and support for her, visiting her abroad during her studies. Dad was all about empowering us.

We were in awe of the multitude of construction projects my dad worked on over the years: from the Lafayette Veterans Hall, to the San Francisco State University Mashouf Recreation Center, to countless high-rise units in San Francisco, where he specialized in door installation. He wore many hats as a carpenter: business owner, commercial developer, foreman, remodeler, housing development, restoring antique architecture, doors specialist; my dad was a journeyman in his field. He enjoyed working, and took great pride in a job well done. For all the talk about Drive fast, take chances, safety third, my dad certainly put safety first on the job site!

But he knew when to play hard, too. My parents took us on many vacations and outdoor activities as kids, from houseboating and waterskiing, to snow skiing in Winter. As a teenager, he started taking me snowboarding at Kirkwood, often with his friend Alan Gray, exploring double black diamonds and more challenging terrain. Over the Winters that followed, I cherished those days spent on the mountain snowboarding with my Dad. Sure, snowboarding itself is simply fun on its own, but it was also the experience of flow through Nature. We shared some of our closest times on the mountain.

One time, while snowboarding at Heavenly, we took a break on the way down to appreciate the stunning view of Lake Tahoe. Sitting in happy silence, he remarked, “Katie, this is our Home. Anywhere in the mountains, outside, is Home”. He had always instilled this philosophy upon us as kids, but growing up into a young adult, it grounded me. Yes, Nature was my home, my playground, and always would be. We had so much fun together out there!

Years later, we did the California Chutes, an incredible day hike off the summit of Kirkwood. After hiking for a couple of hours, we neared the summit. He looked at me with conviction and said, “Katie, this is still Home, but whatever you do, don’t fall here!” It was the most amazing run of my life, a long, powdery, blissful run, finishing out at a lake.

These experiences were not only fun and adventurous, but incredibly formative. The lesson was consistent throughout: life will throw challenges at you. How you respond to those challenges determines your experience. Thus, when you’re on the mountain and it’s snowing hard, blowing sixty miles an hour wind in your face, you’d better be prepared with your jacket, goggles and face balaclava, strength, and a good attitude, lest it ruin your afternoon. It was all about having fun despite the difficult nature of the activity. Perseverance was paramount.

One of Laird’s favorite places besides Kirkwood was the Delta. He spent years waterskiing there, probably with many of you sitting here. It was always fun to wakeboard and go fast over the water, but our best times were often when the engine turned off, when we moored ourselves on some sandy shoal, in the serenity of late afternoon sunlight, the sound of lapping water our keeper of time. We both loved birds, and would see so many amazing ones out there – herons, egrets, hawks galore. My favorite memory was cruising down a slough as a large flight of swallows led our way, hundreds of them picking off insects gracefully, never too close to the boat, just skirting ahead of our bow. This went on for minutes; we looked at each other and said, “Isn’t this magical?” And soaked up the close encounter with these beautiful birds, witness to their grandeur. Yes, it was magical.

I had the gift of time with my dad. Whether it was snowboarding at Kirkwood, wakeboarding on the Delta, hiking around California, or just hanging out talking, I am grateful we made so many memories over the years.

More than anything, he was my best friend; one of the few people I could really talk to. Laird was always keen to learn something new, or share something new he’d just learned. Intellectually stimulating conversation was his cup of tea, and I know so many of you will miss that as well. He cared deeply about the environment, and current events.

He was also a wonderful listener, especially when you were going through something tough. Talking with him is what I miss most; he was a hero in the empathy department. When I went through breast cancer treatment two years ago, he once again was my hero. He came down to see me regularly during treatment, and we shared some of our closest moments during that time – long hikes, beach days, redwood exploration, leisurely lunches outside in the garden. We shared some of our best conversations during that time.

There was one day in particular, when we had enjoyed a nice, long hike, followed by lunch. Yes, I was going through chemo, but darn it, we were making the most of it. Relaxing in my backyard under abundant sunshine, birds flitting about, he turned to me and said, “Isn’t this the life?”

Yes, this is the life, and I’m so grateful I had these moments with you, Dad. I hope everyone here looks back on those moments you shared with Laird and appreciate every one.

When he was in his final weeks of life, I explained to the Hospice nurse what a hero my dad had been for me during my breast cancer treatment; how he had saved my spirit. My dad interjected tearfully: “No, you saved me”.

Being a hero for someone is truly showing up for them; it’s seeing them for who they really are; it’s hearing what they mean behind their words. Being a hero is loving someone unconditionally, with genuine acceptance and warmth. My dad was a hero to so many people in this sense. Loving, generous, Laird loved people. He loved his wife. Wherever he went, he made friends. And he loved being Greatdad. He cherished being with his five grandchildren, and loved them dearly.

In his final days, he commented, “We said it all; we did it all”, of our life together. Yes, we had been blessed with lots of time together; yes, we had the luxury of some time to say “goodbye”. But when it’s someone you can really talk to, there is always something more to say.

In his honor, I encourage everyone who knew Laird to live with curiosity and passion; to take care of business, and then play with even greater focus; to offer yourself fully to every moment; to notice the incessant beauty of Nature, and to protect, appreciate, and fight for it; to be kind; to care about wildlife of every size, from caterpillar to hippopotamus. Notice how amazing our planet is, and how lucky we are to be alive to witness it. Though problems exist, find the light, and cultivate levity.

This leads me to a short reading from one of my favorite books, The Manitous: A Collection of Ojibwe Indian Stories. My dad gave me many books over the years, but this was one of the most impactful, given to me for my fifteenth birthday. The central theme is to respect and revere Nature; to not be greedy with Earth’s bounty; and to build wisdom among generations of humans.

“Just as food is meant for every living being, human and animal, so Kitchi-Manitou set aside and appointed a place and a time for all beings to make homes for themselves and their offspring wherein they could seek shelter from the wind, rain, and snow and take refuge from their enemies. No one was granted primacy or dominion over the Earth or another species.

Indeed, if there is a primacy of any kind, it may well be that birds, animals, insects, fish, and even plants possess a primacy to a greater degree than do human beings, by virtue of their capacity to fend for themselves without assistance from other beings, human or otherwise. With the exception of corn (maize) and perhaps dogs, no animal or plant needs anything from humankind. No such claim can be made of human beings.

Having no need of human beings and endowed with their own natures, attributes, and independence, eagles, bears, butterflies, and whitefish, representing various species of the Earth, are humankind’s cotenants upon the land, sharing the yield and fruit of Mother Earth. Such was the order of life that Kitchi-Manitou’s vision intended and ordained.

But the Earth did much more than serve and fulfill humans’ and animals’ physical needs and appetites. Through all its stages and seasons, Mother Earth inspired and evoked in men and women a sense and appreciation of beauty, curiosity, and wonder and stirred in their souls joy and sometimes gloom. Old men and women often paused to gaze on the sun rising on the horizon as if from the depths of the sea in the morning or to watch it decline in the west in a shroud of crimson to gratify their sense and need for beauty, saying in wonder, “Only Kitchi-Manitou can do that”. In their travels over their lands, the Anishinaubae people saw many spectacles, such as a rainbow at the foot of a waterfall or the dance of thousands of wavelets in a moonlit lake that entranced them and made them long for time to stand still and the vision last forever. Mother Earth was beautiful beyond words, for all time.

Besides beauty, mother Earth also had a spiritual presence, an aura of mystery that imparted a sacred character to certain places. Where but nearer the dwelling place of the Manitous was there a better place from which to address the Manitous and to be addressed by them.

Finally, the last sense in which the Earth was mother, was as a teacher. It was through the changes and beauty of the earth, that the Anishinaubae, discovered the existence of Kitchi-Manitou, and reasoned that the Great Mystery was the creator of all things and beings. Mother Earth revealed by means of her transformations that there is a Kitchi-Manitou and so believed that other Manitous were created by the first mystery and set in the world to preside over the destinies and well-being of every species of living, sensitive beings, by observing the relationship of plants, animals, and themselves to the Earth. The Anishinaubae people deduced that every eagle, bear, or blade of grass had its own place and time on Mother Earth, and in the order of creation in the cosmos. From the order of dependence on other beings, the Anishinaubae determined and accepted their place in relation to the natural order of Mother Earth.”

Thank you all for being here today, and remember:

Drive fast, take chances, safety third, and live like Laird!

***

After the service, many people came up to thank me for capturing the essence of my father’s life, to tell me how much my eulogy spoke to his spirit. One of his old friends emphasized how the words I chose were beautiful, and painted such a vivid picture of his life. Despite the circumstances, it was nice to see old friends and family, and to feel like my words had resonated with people who loved my dad.

It’s been over four months since his passing. I miss him like crazy, and still cry often, but I try to focus on being grateful for all of the time we shared. I got forty-one years with him, and I am lucky for that gift of time. I’ve been busy this Summer mountain biking and hiking around California, trying to live for two people since he can’t anymore.

Grief is a roller coaster of emotions, from acceptance, to anger, to crippling sadness. For he was not just my dad, but so much more. Though he lived to be 71, I still feel like he died too young. He was one of the few people I could really talk to in my life, who would really listen and reflect. I feel more alone now than I ever have, despite having loving people in my life. I feel lost at sea without a paddle, as we’d always been very close.

When my parents divorced in 1996, I moved in with my dad full-time. We lived together for my junior and senior year of high school, and this was one of the best times we had together. From watching Saturday Night Live (our favorite sketch was the “Neat” one – no matter what was said, it was neat); to him taking me out to fancy restaurants and showing me how a man should treat a woman on a date; to going snowboarding at Kirkwood, often with his best friend Alan Gray; to wakeboarding out on the Delta. We became more friends than father-daughter during this time, and it was formative. He helped me with my Math homework, and taught me how to drive a stick-shift on his little Toyota truck we called “The ‘Tine” because it was so tiny; he had to replace the clutch afterward, without expressed complaint, mind you. We jammed on guitar together, strumming tablature from Alice in Chains and Bob Dylan music books, among others. We sang in harmony, laughing at the times we were certainly not in harmony, and progressed as musicians.

When I got my driver’s license, he quipped: Drive fast, take chances, safety third.

I laughed hesitantly; you’re joking, right? But no, he wasn’t really joking.

This was the first of many times he would say this to me and others, which almost felt paradoxical, as he was always super safe when working on his job sites, and didn’t live his life in a reckless, careless way. It was the perfect juxtaposition to his calculated, measured demeanor at work. He would say it whenever someone was about to do something fun, go on an adventure, or take a risk athletically or otherwise. Someone taking off on a road trip cross-country? Drive fast, take chances, safety third. Someone about to drop the California Chutes at Kirkwood? Drive fast, take chances, safety third. Someone leaving Alan Gray’s famous round table? You get the idea. It was a mantra of sorts, delivered in perfect time, encouraging people to get rad; to dive in whole-heartedly to their adventures, to go for it.

After my high school graduation from Acalanes in 1998, Dad and I had a special opportunity to drive cross-country together, spending six days exploring the country along Interstate 70. Bonnie was to do an internship in Washington, D.C., so we drove her car out for her. It was a trip I’ll always remember, how we tasted each state by its tap water (Kansas tastes flat!); how Dad got a speeding ticket in Kansas on his forty-eighth birthday (the cop even told him, Happy Birthday, as he handed him his ticket), to the dramatic lightning storm we saw in Kansas. And that was just Kansas!

Dad had just gotten surgery on his ACL in his knee, and despite the brace he had to wear, crutched around the capitol to see the Smithsonian Museum, Arlington Cemetery, and Lincoln Memorial, among other highlights. When we finally reached the end of I-70 at Ocean City, Maryland, a sign displayed: “Warning: Wild Ponies Bite and Kick”. Wanting to test that a bit, I neared the wild horses, who promptly proved why that warning sign was merited. Snapping my hand back and recoiling from the horse as it bit at me, they reminded me it was their domain.

The best memories of that trip were the conversations Dad and I shared. I was readying for college, all seventeen years of my life getting ready to spread my wings.

When I left for college at UC Santa Cruz in Fall of 1998, Dad dropped me off and said, You sure chose a good place to go to college, Katie. I’ll be down a lot to visit!

Over the following years, he followed through on that promise, coming down to visit me often. Since I was only about an hour and a half away, I visited my parents and family in the Bay Area often, too. We went hiking, to the beach, waterskiing on the delta, and snowboarding at Kirkwood in the Winter. He was someone I called regularly for advice on life, whether it was choosing my major, my boyfriend, or choosing my career path. He was always there for me, day or night. There was always a sense of both adventure and excitement when we would hang out, whether we were doing an activity, or simply talking. This spirit of exploration and appreciation continued over the years that followed, as we shared many days on the mountain, on the water, on the snow. Moments of bliss, moments of awe and wonder, moments of reverence for the world around us.

Dad remarried in 2012 to Ella Wolfe, whom he loved deeply. They shared several sweet dogs: Banjo, Bozzie, Sophie, and Ginger. They lived in Lafayette, Crockett, and ultimately, Smartsville. He retired from working around 2018, but continued working many side jobs. He genuinely loved the challenge of solving a problem, or designing something to be problem-free in the first place.

When I got breast cancer in February of 2020, Dad really stepped up to be there for me. He came to see me almost every weekend, despite being in a pandemic; some days, we only hung out outside, never getting closer than six feet. It was almost a year of treatment before I was “done”, and he was there every step of the way, from the day I cried in the parking lot when my chemo was delayed, to the time I walked up the hill behind our house with him the day after my mastectomy. We shared some of our closest moments during this time, talking about life and death, reflecting on our short time on this Earth. Beach days, redwood hikes, long lunches, and time just hanging out around my house became soul-saving for me. I’ll always revere the day he brought down old photo albums from my grandmother’s teenage years, a glimpse into her life as a budding young woman.

In retrospect, this was probably the closest we’d ever been. We had some of the best conversations about Science. I’ll never forget the day we went hiking at Quail Hollow Ranch, one of my favorite parks. Sitting atop an overlook, we somehow meandered to the topic of surface tension of water. We were known to take many tangents, both on the trail, and in conversation. As a Science teacher and Environmental Studies major, I’ve taken a lot of Science classes in my life, and am a naturalist, constantly studying the natural history of the world around me. Though I might know a few things, there’s a lot more that I don’t know. I love learning, like Dad did, so it was always easy to talk about anything, really. We challenged each other intellectually and thrived while learning from each other.

Sitting on a bench in the Santa Cruz Mountains, I explained how water is a polar molecule, with an imbalance of positively and negatively charged particles at either pole, causing it to seek balance by adhering to other water molecules, the basis of surface tension – you know, why it hurts when you belly flop into a swimming pool, or how plant roots intake water through capillary action.

He turned to me and said: I’ve always thought of myself as the “teacher” in our relationship, you know as father and daughter over the years. But now, you’re teaching me.

It wasn’t the first time I’d taught him something, of course, but it was a fitting observation. I always say that my dad saved me during treatment. He reminded me of my tenacity, enthusiastic spirit, and appreciation for life and nature. My husband Ron mused that Dad had taken my cancer from me, metaphorically speaking, but I never thought he would have actually taken it from me. That’s not possible, of course, but it was a fitting metaphor based on what happened next. He may just have had cancer at the same time that I did.

In Fall 2021, he told me he wasn’t feeling very well altogether: fatigue, headaches, and an overall feeling of malaise, like something was really wrong. So began the doctor’s appointments, and bloodwork. His white-blood cell count was elevated, so he pushed his doctors to investigate further. They ordered an abdominal ultrasound, which detected a mass on his liver. This was followed up weeks later with a CT Scan, which confirmed the mass. He was then scheduled for a biopsy.

He continued to feel worse, feeling so weak he could barely lift anything heavy, nor could he do the activities he used to love. He would get uncontrollable hiccups after eating or drinking. Everytime I spoke with him, he relayed how exhausted and ill he felt. February 12, 2022, was the last “normal” day I spent with my Dad, and he clearly said: I don’t know what this thing is, but I can tell it’s not good. I’ll fight if there’s a chance, but if it’s too late, then I’m at peace with that. I’ve lived a good life, and maybe it’s just my time. I knew sitting next to him right there that he was right; that he was facing something insurmountable, and perhaps accepting it was all there was left to do.

Several days later, my older sister Bonnie and her children went to visit him over Presidents Weekend at his house in Smartsville, California, in the Sierra Nevada foothills. They had enjoyed a pleasant evening together, before my dad woke Bonnie up in the middle of the night. He couldn’t hold down any water, had the hiccups, and felt like he was so dehydrated he was getting delirious. Bonnie drove him to the Emergency Room at Sutter Memorial Hospital in Grass Valley. He was admitted and given more diagnostics, including a brain CT scan; that’s when the doctors realized he had a large brain tumor on his cerebellum, and that his headaches were likely from the swelling taking place under his skull.

Doctors assessed his overall situation and offered a few treatment options, with little guarantee they would do anything to help. They could cut into his skull to relieve pressure, and try radiation on his head to shrink the tumor; this could cause permanent brain damage, and if the surgery worked, the radiation side effects would be crushingly painful. Then, they would have to address his liver and stomach tumors and all that would entail.

It wasn’t long before Dad accepted there really wasn’t much that the doctors could do at that point, and they were clear about that. Stage 4 terminal cancer was his diagnosis, and it was basically too late to do anything about it. They predicted he may have days to weeks to survive. My dad averaged that prognosis and proclaimed he may only have two weeks to live. This was on Saturday, February 19, 2022.

I got the phone call from my sister Bonnie telling me the news; perhaps Dad had only two weeks to live. Waking up from a deep sleep, I was shocked at how little time he was given. Two weeks?!

The hospital didn’t allow visitors at first due to the pandemic, but considering the situation, allowed us. Bonnie and I drove up there together on Monday. Dad was sleeping soundly, but awoke to our presence. We didn’t say much; we held his hand, and tried to be as quiet and peaceful as possible. The last thing he needed was any added grief or stress. We talked occasionally, but mostly sat in relative serenity for about an hour before we left. Something about holding his hand that day, with his gentle occasional squeeze, felt like a blessing amid a heartbreak, and I soaked up that moment.

I drove back up on Wednesday that week, and sat with Dad a while, mostly in silence, not wanting to disturb him. I spoke with the nurses, who urged us to transfer my dad from the hospital to home, where he could receive Hospice care.

Wouldn’t he rather die at home? They asked. My dad was reluctant to leave the hospital; he felt safe and comfortable there. He was losing mobility and strength, and having trouble standing and walking. With a little bit of prompting, Dad agreed to leave the hospital. My sister Bonnie lives in Lafayette, and graciously – and heroically – offered to have my dad come there.

Thursday morning, bright and early, I showed up at the hospital to take him home. Carefully situating him in the passenger seat of my Subaru Outback, I set out on the most important drive of my life. He had been given a sedative, so was quite sleepy, but occasionally interjected along the drive home. Santana, he offered, as Oye Como Va played on the radio. I tried to keep the music at a reasonable level, as I know how much he loves music, but didn’t want to give him a headache.

I saw his eyes wandering out the window along the way, and it struck me how he must be looking at the scenery realizing it would be the last time. Last drive over the Yolo Bypass; last drive among the rolling, green hills. What a bitter pill to swallow, even if he had said he was “at peace” with his diagnosis. I cried behind my sunglasses as I felt the gravity of how many “lasts” he was experiencing, and how it might feel to be cognizant of that. Somewhere along the drive, he reached out and grabbed my resting right hand and squeezed it tightly. Again, there was something peaceful and settling about his hand in mine.

After about two and a half hours, we reached Bonnie’s house in Lafayette. A hospital bed had been delivered, as had a wheelchair, walker, bedpans, and many other toiletries. With some help from a Hospice nurse, we slowly helped my dad to his bed. My sister Mary was there, too, and all three of us braced ourselves for a journey we had no idea how would unfold.

I took time off work and left plans for a substitute. I didn’t know how long it would be, but I knew I wouldn’t be anywhere else on the planet.

In those first few days, there was a lot of sleeping, but also some glimmers of hope. My dad would eat a little bit of food, and was pretty talkative with all of us. Ella had come down to be with him as well, and that gave him great comfort. He also saw his two dogs, Bozzie and Ginger, who fervently licked his face and cuddled up with him when they saw him. Clearly, they had missed him over the last week. Dad couldn’t get out of bed anymore, so we were helping him with all kinds of things. Hours were spent sitting with him in his room; I wrote in my journal, did crossword puzzles, and read while he was asleep. When he was up, I delighted in anything he said, whether it was commenting on how loudly the dogs snored, or how much we had meant to him in his life. There were many tearful conversations, reminiscing over old memories, and mourning all the memories we wouldn’t be able to make, balanced with lighthearted moments and even laughter. Some I hold too close to my heart to even try to express in words or share with others, but I hope by sharing some of these moments it might help others taking care of a dying loved one. It was the hardest, most intense thing I’ve ever done.

It wasn’t the time for us to feel sad, though. It was Dad who was depressed, with reason. Duh! Of course he would be, just given days to live. We knew there was something wrong before his diagnosis, but we’d all thought there might be some kind of “fight”, where we would try surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, something. To be told, basically, that there was nothing to do except wait to die, was a gut punch, literally and figuratively. He was crestfallen, and it was hard to see him give up, however much he knew that was the only thing to do.

After a few days of being at home at Bonnie’s, Dad started saying how he wished he would just die; that he couldn’t wait to have that relief. He had remarked to Ella one night, half-jokingly but mostly serious, that we probably couldn’t wait for him to die; that caring for him must be such a burden. I couldn’t bear the idea of my dad thinking he was a burden to us. When I spoke with him next, I had to dispel that assumption.

I told him that I needed him to understand something important:

You know all those times you took care of us over the years? Not just as children, but as adults? Well, now it’s our turn. I need you to understand what a gift this is to us, Dad, and how lucky we feel to be here with you. This is an honor to get to be here with you, to get some extra time together. You are our hero, so any extra time we get with you is a true blessing. This is not a burden to us, but an honor.

He teared up, feeling the love, but also the gravity of the situation. Yes, he was dying, and yes, his daughters and wife were taking care of him. I hoped he understood what a true honor we felt this to be.

Hospice was very helpful, by the way, but it wasn’t the full-time care I had assumed. They train you how to do everything, and then leave. I’m not complaining; I was just a little surprised by how much you really need to do on your own. I had assumed hospice care involved having someone there most hours of the day, but you have to pay a private nurse for that level of care, apparently.

Nights were a bit challenging. About a week in, we hired a night nurse to sit with him so we could all get a good night’s rest. They were there from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m., and it was extremely helpful.

Dad stopped eating food, and started sleeping a lot more. We had time to say “goodbye”, and reminisce about old times, but once he started saying how he just wanted to die, I felt like I wanted that relief for him, too.

His headaches were getting worse, likely from the cerebral edema he was experiencing. His forehead would get extremely hot; we rotated ice-cold, wet washcloths on his forehead, changing them as often as every thirty seconds at the worst of times. It is really heart wrenching to watch a loved one suffer in pain. This was the hardest part, but obviously it was harder for him experiencing it. We all wanted him to have some relief, to be free of suffering.

Hours were spent by his side, the only place we wanted to be. We would take breaks during the day to get out and do something as a release; my escape was going trail running or hiking at Briones, just up the road from Bonnie’s. It was the time where I could get away from it all, and let myself have a good cry. It was my time to process everything, and reflect. I felt my dad with me on these hikes, knowing he would be with me otherwise. Wildflowers were just starting to bloom, the hills were emerald green, and the best part was spotting a pair of mating newts! I was able to watch them for about fifteen minutes, sitting still alongside the creek, marveling at their beauty. It was a real blessing to witness! I also saw my old friends Orla and Shanna with their husbands one day, the best surprise. I’ve known them since I was young, and seeing their faces made me feel calmer.

I listened to Justin Bieber’s Ghost so many times, driving in my car singing at full volume a song – and music video – that spoke so directly to me. I still listen to that song often, and think of my dad every time.

As the days passed on, Dad became increasingly despondent, and slept most of the day. He said he just wanted to die at least a few times each day. I actually told him something I never thought I would utter: Dad, I hope you die today, with a loving smile, and he said, Me, too!

A couple of more days passed, and then, on Saturday, March 5, 2022, things took a turn for the worse. I had just gotten back from a run at Briones, and I admit, it was a tough one. I’d forgotten food and water, and had gone too far down the trail before turning around. It was one of those two hour runs that just doesn’t seem to end. Exhausted, hot, hungry, and facing yet another steep hill (Briones is famous for them), I shouted out into the air:

I hate this place! I don’t want to run here anymore! After ten days of conquering the unrelenting hills that comprise Briones, I was tired. I didn’t want to climb another hill; I wanted something flat and easy. It was the perfect metaphor for the hard time we were all going through. Famished and thirsty, exposed under the punishing sun, the trudge back to my car was a long one. I was beat, and said to myself, This is the last run I’m going to do here for a while. I need a break from this place – a prescient statement, really. That would be my last run there after all, for the time being.

When I got back to Bonnie’s that afternoon, Dad began throwing up blood. We gathered around him, and stood by his side as he threw up blood into a towel which I would hold under his mouth. We called the Hospice nurse, and understood now that a line had been crossed; there was no turning back from this. Dad was dying, right before our eyes. I share these details not to be sensational, but because it was shocking at first; nothing really prepares you for it. Death can be swift and serene, or long and turbulent, and everything in between.

I’d often repeated a mantra to him: Endless Kirkwood powder, and glassy Delta sloughs forever, imagining what Heaven, if there were one, might look like for him. As he lay there vulnerably, we comforted him as best we could, told him we loved him, to be free and fly.

Endless Kirkwood powder, and glassy Delta sloughs forever, I said again.

This went on for about two hours, by which time the nurse had arrived. With some encouragement, Dad finally agreed to pain medication; he had resisted all this time. We administered morphine and Ativan, and within twenty minutes, he had relaxed quite a bit, not throwing up blood anymore. He coughed again, and Mary and I both were at the ready with towels. He joked: Cough once, get two daughters. This was the last thing he ever said directly to me, and I’ll never forget it. He fell into a deep sleep after this, never fully waking up again.

We continued administering morphine and Ativan throughout the night and next day, and Dad continued to sleep heavily. He twitched when touched, as if recoiling; he didn’t seem to want to be touched anymore. We sat with him still, hoping he would soon find the relief of death. His breathing slowed, with long periods of apnea.

Around 3 p.m. that day, I left to go back home to Ben Lomond. I hadn’t been home in twelve days; hadn’t seen Ron, or cat Beau, and of course I hadn’t been at school for two weeks. I decided I would go back to work on Monday, set up sub plans for the week, and go back up to Bonnie’s that afternoon. Knowing my dad’s condition, though, I knew he was already gone. I knew on that drive home that it was only a matter of hours before he would pass. I got a phone call around 1:15 a.m. that night that Dad had passed, sleeping peacefully. It was a strange combination of both relief that he wasn’t suffering anymore, and grief that now it was actually final.

It’s hard to express what those following days were like. Bonnie wrote a gracious obituary; Mary and I started planning the memorial. I was deeply grieving, exhausted from the last couple of weeks, and starting to accept the permanence of it all. I felt like I’d lost the one person in my family that knew and understood me the best.

When my dad lost two very important people in his life – one of his best friends Alan Gray in 2010, and his mother Sheila in 2019 – he remarked, Who am I going to talk to now?

He didn’t mean he couldn’t talk to anyone else, but was merely acknowledging how much he loved talking with those two. Back in the day, we used to spend hours sitting around Alan’s round kitchen table, sharing conversation that bounced from tangent to tangent in the most organic, beautiful way. I long for those conversations. It was the same with my grandmother; I would visit her, often with Dad, and would look forward to the path our discussions would take.

That is exactly how I feel now that he is gone; who am I going to talk to now? Yes, I can talk to others, namely my amazing husband Ron, but there is no replacement for Dad. He was the one I gravitated toward at family events; the one who was always proud of me, regardless of whether I had kids or not, whether I was wealthy or not. He was the person who not only saw and heard me, but understood me. We were so much alike, truly kindred spirits, like two peas in a pod.

One of the last texts Dad ever sent me went something like this. I’d forwarded him an article about the last Irrawaddy river dolphin dying in northeastern Cambodia, part of our usual doom-and-gloom sharing of environmental news. We regularly lamented about the sad state of the world with climate change and a slew of other depressing plights of humanity. I added that the planet was fucked, and we humans have got to go.

He replied back that he found it most interesting that I, along with his other close friends in life – Jim, Danielle, Alan, Kent, Quynh – all decided to go childless. This is what I’ll miss most about my dad: the way he saw me for who I was.

I wrote him back thanking him for acknowledging this, as not everyone sees it that way; many people look down on me as a less fulfilled person because I chose not to have kids (what a waste of ovaries!). I reminded him of the moment I chose not to have kids, sitting in my senior year of high school talking about the human population nearing six billion. I proposed, half-jokingly, that two-thirds of the world’s population volunteer to kill themselves off, to ameliorate the environmental problems we were experiencing. I said I’d be one of those volunteers, willing to sacrifice myself for the greater good. Of course, that’s a violent and unrealistic proposal, but in a seventeen year old’s mind, it seemed so simple. He replied that he and his friend Jim Hale had spoken recently about the dire state of the planet, that we’d reached a point of no return.

Yet nature’s beauty persists, drawing us to those wild places, like the mountains Dad loved.

Three months after his passing, on June 7, 2022, I won the lottery to hike up Half Dome in Yosemite. It’s such a popular hike that’s been nearly loved to death, so now the park must regulate us humans; no more than 300 people per day can ascend the Half Dome cables. I was stoked to gain entry, and set out on an epic hike at 6:30 a.m. It was about five hours of hiking uphill to reach the cables; then, about thirty minutes to get up the cables. There was some traffic, and it was a slow ascent; obviously, no one wants to rush here! You fall, you die.

The summit was overwhelmingly vast and stunning. I thought how Dad would be there with me if he could, and how he’d hiked it himself some 51 years earlier. It was the hardest hike I’ve ever done – 17 miles, 9.5 hours start to finish – but an incredible one. It felt like a fitting way to honor my Dad, who loved the Sierra Nevada mountains, on the three-month mark of his death.

When Father’s Day came on June 19, it had been exactly one year since he had come to Big Bear with me. I had a downhill race at Snow Summit last year, and he came to watch; we spent a splendid weekend together. This year, I went back, and it was as hard as I thought it would be. Memories everywhere I looked, from the restaurants we ate at, to the bench we sat on after the race. It was my first Father’s Day without Dad, too. I cried often during the weekend, especially on that special Sunday I used to share with Dad. I had planned to race that day as I did last year, but couldn’t bring myself to.

I am reminded of him everywhere, from being outside in Nature, to birding, to Science current events, to my observations of daily life; to the restaurant we last ate at together in Truckee – Jax at the Tracks, when I was up at Northstar – to the hikes we used to take around here.

I’m reminded of him when I see his favorite bird, the chickadee. Chickadees are some of the most social birds around, and are fearless in their disposition; they are curious, smart, and crafty. Dad always talked about how much he loved them – mountain or chestnut-backed – and every time I see one now, I am reminded of him.

I’ve been hearing my dad through music, too, something that always connected us. We loved playing guitar together and sharing our favorite songs. I’m hearing “our songs” everywhere I go. I was missing him on a road trip recently and stopped at a gas station; in the restroom, the song In Your Room by The Beach Boys played over the speakers. This was his favorite Beach Boys song. When I listen to the radio in my car, an old Alice in Chains or Sublime song will come on just as I’m thinking about him; when I hear 311’s All Mixed Up, I remember him mocking our senial cat Sam in his old age. When I’m playing an old song we used to play together on the guitar, I feel him there. I’m not superstitious, but I can’t help notice the connection. I was stuck in traffic the other day behind a car with a bumper sticker that read “Make Safety Third Again”, knowing how my dad would love it (apparently there’s a backstory to this slogan involving Mike Rowe).

Dad loved being outside in Nature, music, learning, exploring, but he loved people just as much. Anyone who ever met him knew how he made friends everywhere he went; how he could spark up a genuine conversation with anyone, no matter their background or political leaning. He thrived off connection with others, and loved the lively banter that unfolds when people come together. He was empathetic and a great listener, and could make you feel like you were the only person in the room when you were talking. I think of all the people whose lives he enriched; he had so many friends, acquaintances, work buddies, tradesmen, coffee shop baristas, family, you name it. When you met Laird, you remembered him.

As extroverted as he was, he loved his quiet time, too, specifically for study – be it literature, or observation. He was a voracious reader, mostly science, history, politics, and works of nonfiction. He was the epitome of a fierce intellectual. We shared a love of knowledge and learning, especially about Science. Dad gave me several books over the years, like A Year on the Wing, the last book he gave me, or one of my favorite books he gave me during cancer treatment, What It’s Like to be a Bird, by David Allen Sibley. Each book influenced me, but the Tao te Ching and The Manitous were perhaps most impactful. I read these as a teenager looking for my place in the spiritual world, having long realized I did not believe in God, nor the Christian faith under which I was raised. These books resonated strongly with me, and to this day influence my life. Namely, they taught me the power of detachment, ownership, and taking accountability for your actions and thoughts; that I am small in the best way; that I am a tiny part of an incessantly vast, beautiful universe that lives on with or without me. I know that he, too, found comfort nestled in this cosmic perspective.

This Winter, when conditions are right, I will travel to Kirkwood to a special tree only a handful of people know the significance of. You have to snowboard down a challenging run to get there. Alan Gray’s ashes were scattered here in 2011, at home in his favorite place, and I will bring my dad’s ashes up there to join him soon.

I think of all the people who knew him, how many lives he graced with his presence. Everyone who knew him has their own intransmissible memories, a shared network that bonds us together. In the roll call of Life, we will always note the absence of Laird Buchanan Craig, an irreplaceable spot on a sacred roster. I’ll always reach out for his hand, hoping for a gentle squeeze back.

In his honor, I encourage everyone who knew Laird to live with curiosity and passion; to take care of business, and then play with even greater focus; to offer yourself fully to every moment; to notice the incessant beauty of Nature, and to protect, appreciate, and fight for it; to be kind; to care about wildlife of every size, from caterpillar to hippopotamus. Notice how amazing our planet is, and how lucky we are to be alive to witness it.